The Elephant in Waiting

In 1975 Willets, the owners of the Elephant and Castle shopping centre, sold it to Ravenseft Properties. In 1978 the new owners completed a refurbishment, which converted the third level of the centre to office space, provided glazed panels on the previously windowless facades and moved the Elephant bronze outside99. A spokesman commented at the time that, "one has to do something when one has inherited such a horrible asset."100 This was the first in a long series of initiatives and proposals to regenerate the area, which were to colour the 1980s and early 90s.

The election of the Thatcher government in 1979 brought a new rhetoric to the political landscape. The Conservatives attacked the principles of central planning control and broke down the post-war consensus, cutting back on state interference and expenditure. They replaced it with a set of economic values that promoted competitiveness, freedom, choice and initiative.101 The comprehensive plan of 1951 was replaced at the Elephant with no plan. In 1986, despite large scale protests, the GLC was abolished and the language of the public sector was replaced by that of commercial opportunism and the market. The Elephant became a series of sites open to enterprise, without any overall vision for the place.

Figure 62In 1988, after a sustained period of neglect, the Elephant and Castle Subway Art Project was launched. This included new lighting and retiling of the notorious subways with a series of murals depicting local life and reflecting the Elephant's multiculturalism (see fig 62). It was part of a 400,000 scheme of cosmetic environmental improvements in the area, which attempted to make conditions adjacent to the road bearable.102 In the same year a crucial chunk of the 1960s scheme was lost. Erno Goldfinger's Odeon cinema was wilfully demolished at speed by site owners Imry to prevent listing and in order to facilitate future redevelopment of Alexander Fleming House.103

Figure 62In 1988, after a sustained period of neglect, the Elephant and Castle Subway Art Project was launched. This included new lighting and retiling of the notorious subways with a series of murals depicting local life and reflecting the Elephant's multiculturalism (see fig 62). It was part of a 400,000 scheme of cosmetic environmental improvements in the area, which attempted to make conditions adjacent to the road bearable.102 In the same year a crucial chunk of the 1960s scheme was lost. Erno Goldfinger's Odeon cinema was wilfully demolished at speed by site owners Imry to prevent listing and in order to facilitate future redevelopment of Alexander Fleming House.103

In 1990 Southwark Council made the Elephant and Castle a Regeneration Area.104 The title bestowed some tax relief and favourable terms of planning for new development. The idea was one of a number of Conservative-inspired policies that bypassed the remnants of the planning system. The decline of the Inner City in the late 1970s led to the creation of 'Urban Development Corporations' from 1979, that took land out of local authority control and primed it for sale to the commercial sector bypassing normal planning controls.105 At London's Docklands this example was applied to a huge area,106 which eventually came to a climax in the construction of Canary Wharf. The basis of regeneration was a thriving property market, with regeneration benefits coming from a 'trickle down' effect.107 At the Elephant and Castle, lessons from Docklands were applied on a much reduced scale. In 1992, a building at the long derelict northern Site 3 was finally completed. Despite calls from some in the architectural profession to produce a tower,108 in order that the area may finally achieve some dignity, Skipton House, a low rise building by Paul Cayford for Swedish developers Allhus, was built. Clad in fashionable pink marble and granite the building made full use of the site by ignoring the established geometry, but made no statement of its existence to the rest of the area except for a curving atrium roof line (see figs 63 & 64).

The shopping centre was refurbished yet again by new owners UK Land in 1990, with an emphasis on producing a new Elephant, "quickly, painlessly and effectively."109 Its exterior was painted an attention grabbing 'shocking pink' and the entrance was highlighted with a tension fabric pavilion by architects Harrison &Patience.110 Figure 65

Figure 65 Figure 66

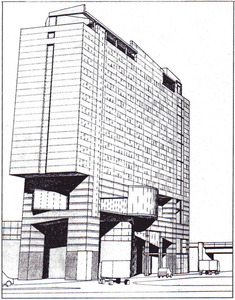

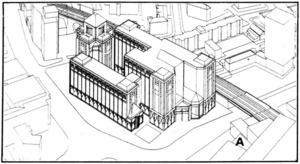

Figure 66 Figure 67 In order to bring back some visible commercial activity the market stalls were moved to the spaces outside the shopping centre (see figs 65, 66 & 67). "Now,"commented a UK Land spokesman, "when the people look out of the thousands of office windows opening onto the roundabout, they see a busy shopping centre full of interest," and with eerie familiarity added, "it will become a prime shopping nucleus for South London."111 In 1991, the new owners launched ambitious plans to build a blue striped, 464 bedroom hotel over the southern end of the shopping centre by architects Raglan Squire (see fig 68). It was approved by Southwark Council, though faced opposition from the Department of Health and Social Security who, as tenants of the neighbouring Hannibal House, feared increased rents if a regeneration scheme was successful.112 In the same year extensive plans were launched for Alexander Fleming House by Imry developers with architects Fairhurst. Having already cleared away the cinema, they proposed greatly expanding the building with a series of "vulgar and inadequate"113 Caesar's Palace style gimmicks and architectural cladding (see fig 69). The scheme also won approval from Southwark Council who in the same year announced proudly that 140 million worth of private sector investment had been attracted and heralded an economic turnaround at the shopping centre, whose visitor numbers had increased by 25%114 to reach their highest ever. However, later in the same year bailiffs were ordered into the centre to evict shop owners who refused to pay new rates of tenancy, some as much as double the year before.115 The recession had begun to bite and a brief period of boom was over. All development proposals came to a halt.

Figure 67 In order to bring back some visible commercial activity the market stalls were moved to the spaces outside the shopping centre (see figs 65, 66 & 67). "Now,"commented a UK Land spokesman, "when the people look out of the thousands of office windows opening onto the roundabout, they see a busy shopping centre full of interest," and with eerie familiarity added, "it will become a prime shopping nucleus for South London."111 In 1991, the new owners launched ambitious plans to build a blue striped, 464 bedroom hotel over the southern end of the shopping centre by architects Raglan Squire (see fig 68). It was approved by Southwark Council, though faced opposition from the Department of Health and Social Security who, as tenants of the neighbouring Hannibal House, feared increased rents if a regeneration scheme was successful.112 In the same year extensive plans were launched for Alexander Fleming House by Imry developers with architects Fairhurst. Having already cleared away the cinema, they proposed greatly expanding the building with a series of "vulgar and inadequate"113 Caesar's Palace style gimmicks and architectural cladding (see fig 69). The scheme also won approval from Southwark Council who in the same year announced proudly that 140 million worth of private sector investment had been attracted and heralded an economic turnaround at the shopping centre, whose visitor numbers had increased by 25%114 to reach their highest ever. However, later in the same year bailiffs were ordered into the centre to evict shop owners who refused to pay new rates of tenancy, some as much as double the year before.115 The recession had begun to bite and a brief period of boom was over. All development proposals came to a halt.

The period leading up to the recession had seen a rash of quick fixes and garish private sector proposals all designed to squeeze the Elephant. Although investment may have reached new heights, the commercial sector clearly wanted a quick return from the minimum of investment and in the economic hype little consideration was given to addressing the long-standing environmental conditions in the area. The slump highlighted the same old problem. The road scheme still dominated the Elephant and Castle in an inner city area that deterred many. It was trapped between London's congested, expensive core and its detached outer edge. It was at the edge that the car would give rise to a new landscape in which vehicular traffic would be encouraged.

The Conservative government gave the car a much more overtly political dimension. The party of freedom and the individual seized the symbolism of the automobile. "The private motorist," said Tory Secretary of State for Transport, Nicholas Ridley in 1984, "wants the chance to live a life that gives a new dimension of freedom - freedom to go where he wants, when he wants and for as long as he wants."116  Figure 68

Figure 68 Figure 69The economic boom in the 1980s had been fuelled in London by the deregulation of the financial markets in the City. There emerged a new era of conspicuous consumption, characterised by the yuppie, where the car was central to status and, increasingly, national prosperity.

Figure 69The economic boom in the 1980s had been fuelled in London by the deregulation of the financial markets in the City. There emerged a new era of conspicuous consumption, characterised by the yuppie, where the car was central to status and, increasingly, national prosperity.

In 1985, the Department of Transport budget for roads went from 1.5 to 2.5 billion;117 By 1989 it would rise to a staggering 12 billion.118 Roads were central not only to Conservative transport policy, but to a whole system of economic linkages. In 1986, at the edge of London, the M25 orbital motorway (the long-standing Ringway 3, see fig 59) was opened amid much celebration for the UK's 16 million motorists,119 while in the same year the Department of Transport subsidy to the city's buses and tube was halved.120 The effect was that in the 1980s, London was characterised by its widening contrasts. Both economically and topographically, two images of the city had emerged. While the inner city was in decline, its population condemned by reduced public services, crumbling monoliths, disused industrial sites and rioting,121 the suburbs at the edge city were thriving with a network of new roads connecting private housing estates to out of town shopping centres, malls and hi-tech industry. The car, under market conditions, created a landscape coloured less by architectural innovation and more by public aspirations that had much in common with the derided ribbon developments of the pre-war era. The new service economy, built up around the roads or corridors, was distinctly anti-urban and rejected the bold, multilevel architectural forms of the post-war automotive age.  Figure 70There was no pressure to mix uses. In the suburbs, and adjacent greenfields, the car and its advocates had the room they wanted. They wrapped themselves in the language of the vernacular: housing once more drew from a much used palette of tudor-bethan, supermarkets were built as giant tithe barns and shopping malls resembled toy towns at the centre of vast, sprawling, landscaped car parks (see fig 70).

Figure 70There was no pressure to mix uses. In the suburbs, and adjacent greenfields, the car and its advocates had the room they wanted. They wrapped themselves in the language of the vernacular: housing once more drew from a much used palette of tudor-bethan, supermarkets were built as giant tithe barns and shopping malls resembled toy towns at the centre of vast, sprawling, landscaped car parks (see fig 70).

Conservative prosperity, of roads, suburbs and out of town sites, left the Elephant and Castle and its contemporaries as a fringe location both in terms of access and in the Tory imagination.

Footnotes

- ↑ The bronze statue of the Elephant, originally from the roof line of the 1898 pub, was a feature of the indoor shopping centre.

- ↑ South London Press, 1975. "White Elephant Has a Massive Face-Lift." Such comments make one question quite why Ravenseft chose to take the Elephant on.

- ↑ Thornley, Andy, Urban Planning Under Thatcherism: The Challenge of the Free Market, 1991. p.37.

- ↑ " Elephant &Castle Subway Art Project" 1988/89 Leaflet and The Southwark Sparrow, October 18th, 1991.

- ↑ The Architects' Journal, August 31st, 1988. p.6.

- ↑ The Trumpet, Elephant &Castle Shopping Centre publicity brochure, August, 1990.

- ↑ Thornley, Andy, 1991. p.162.

- ↑ Ibid. The London Docklands Development Corporation were initially given 870 acres of public land to sell.

- ↑ Rogers, Richard, Cities for a Small Planet, 1997. p.113.

- ↑ "Object Lesson" in The Architects' Journal, June 14th, 1989. pp.26-33.

- ↑ The Trumpet, August, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Trumpet, August, 1990.

- ↑ "E&C Blue Hotel Meets Government Opposition." Building Design, July 7th, 1991. p.6. Very odd situation. Central Government opposed to regeneration at the Elephant and Castle to safeguard cheap rent for its departments.

- ↑ James Dunnett 'Architects Stung into Total Redesign for Goldfinger Site' Building Design, June 28th, 1991.

- ↑ "Minister Sees Elephant Stampeding to Success." The Southwark Sparrow, February 22nd, 1991.

- ↑ "Shop Keepers Defy Charges" South London Press, July 30th,1991. The report provides details of one store, Bodyline, whose rents went from 1,900 to 4,060 pa.

- ↑ Hamer, Mick, 1987. p.66. Quote taken from New Statesman 1984.

- ↑ Hamer, Mick, 1987. p.66.

- ↑ Docherty, Iain &Shaw. Jon, A New Deal for Transport, 2003. p.80.

- ↑ Hamer, Mick, 1987. p.2. Figures based on 1987.

- ↑ Ibid. p.6.

- ↑ Brixton 1981. Tottenham 1985.