The Elephant Resurgam

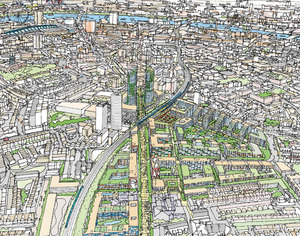

The stagnation of the 1992 recession brought about a degree of reappraisal on policies affecting the built environment in London. Free market policies, had produced a haphazard arrangement of office developments and housing in reactionary pastiche, popular with commercial developers and had contributed to a breakdown in a sense of civic unity, direction and pride. There was sharp criticism from within the architectural profession of a London which, "since the early 1980s has failed to convince its own citizens that it can offer a healthy, secure and humanising environment."122 The response was a call for a new consensus for rethinking the city, in order to address social and environmental imbalances. It was once again possible to talk in terms of the public realm, of "government direction...designers and the active involvement of the citizen."123 By the late 1990s, the architectural climate had moved far from the days of the previous boom, and innovative and co-ordinated design was both permissible and desirable. After the unsatisfactory period of flux of the preceding twenty years, London entered a new period of prosperity and it was to be creatively led from the inner city, quite literally so in Southwark. Figure 71

Figure 71 Figure 72

Figure 72

In 2000, the Tate Modern opened its doors in the converted Bankside power station. It was to become Southwark's anchor project, charged with addressing the cultural imbalance between the two banks of the river and acting as a catalyst for future investment. It was symbolic of the growing importance of cultural and tourist industries to London's overall economic output. Tate Modern had been part of the 'Southwark Design Initiative' in 1996.124 As part of a borough wide review, Southwark Council had also commissioned Pierre D'Avoine Architects to rethink the Elephant and Castle. The Elephant had last been newsworthy in 1993 during the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry at Hannibal House, "with the [shopping] centre itself - then a schiaparelli pink - as absurd pantomime backdrop in contrast with the crowd scenes and clashes played out before it."125 The D'Avoine plan would contribute to altering perceptions of the inner city that had suffered for years. It was to be design-led regeneration. Their proposal was for an "Urban Pier" that would unite the Elephant via an upper level pedestrian deck running its length between Skipton House and the Draper Estate (see fig 71). It was the type of scheme that ought to have been built as part of the 1960s original, successfully segregating traffic and people and opening up vistas across the space. The Buchanan Report would surely have looked favourably upon its implementation. Figure 73

Figure 73

In 1997, St George Developers completed a refurbishment of Alexander Fleming House and it was divided into residential apartments. Metro Central Heights, as it was renamed, retained the Goldfinger building after a long drawn out preservation battle, but the developers were allowed to paint the concrete building a creamy beige (see fig 72). The St George brochure at the time described London as, "happening, crazy, sexy, cool,"126 and made much of its surprising proximity to the West End and the City rather than the merits of the local area. Its new name was deliberately non-specific. Across London the age old transformation of residential accommodation to industrial use was reversed127 as deindustrialization meant vast tracts of the city were available for conversion into lifestyle flats and luxury apartments. In the same year the Pierre D'Avoine scheme was abandoned, but it had widened the scope as to what might be achieved and with a new property boom people were once again talking about the possibilities at the Elephant and Castle.

In 1998 Southwark Council, mindful of a commercial drift southwards, polled its tenants at the adjacent Heygate Estate for their opinions on the Elephant and Castle. They each received cards asking them whether they thought there should be major redevelopment at the Elephant and Castle. The council received 94% vote in favour of redevelopment.128 Out of 11,000 cards sent out the council received 700 back.129 With this dubious mandate from local people the Council launched the most ambitious scheme of redevelopment yet seen at the Elephant which forms the basis of the current proposals.

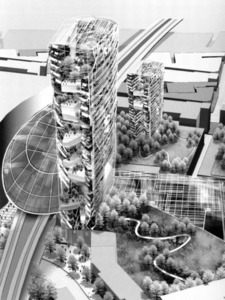

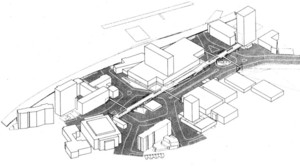

In 1999 Southwark Council launched its proposals inviting developers to submit plans on a 69 hectare area, telling them it was a 'blank canvas,' on which to work.130 It told them any scheme ought to be a 'demonstration project of government policy on education, healthy living, integrated transport and welfare to work.' It was to be a "beacon for regeneration."131 Developers would have to be working partners with the local authority in order to be involved. This was essential as Southwark Council was the majority landowner. It controlled nearly all the sites at the Elephant, some 100 out of the 170 acres132 and was keen to "release" what its development director would later refer to as, "the latent value locked up in the land beneath."133 That year three shortlisted candidates emerged: London & Amsterdam Countryside, who had been responsible for Bluewater in Kent, with a masterplan headed by architects Terry Farrell and Michael Hopkins (see figs 73 & 74); Southwark Land Regeneration (SLR) with a plan overseen by Foster Associates and Ken Yeang (see figs 75, 76 & 77); and the St George Consortium headed by the residential developer St George with a small scale conversion scheme by architect John Thompson.134

In 2000, Southwark Land Regeneration were awarded the contract of implementing their masterplan with the council.135 The development would consist of a new tri-partnership arrangement. At the planning table there would be SLR, Southwark Council and a new group, Elephant Links, who would represent the local population.136 As soon as talks began the plans hit trouble.  Figure 78

Figure 78

The role of the local population in talks was always going to be delicate. Not least because the crux of the scheme involved the demolition and sale of the Heygate Estate to commercial developers in order to fund infrastructure improvements such as transport and council accommodation elsewhere. Objections were raised over the council's refusal to offer tenants any 'right of return' and their reluctance to make clear how they would balance the 1,212 lost residences with the 700-800 proposed for the new development.137 Crucial components of the scheme, so-called 'Eco towers' (see fig 77) or "money makers,"138 were objected to on the grounds that they would block light to, and the view from, neighbouring areas. Further attacks were launched over the scheme's large underpass for through-traffic and the domination of the scheme by a giant covered shopping mall, a financially risky mega-structure (see fig 75). In 2002, talks broke down on all sides. The Council and SLR were in conflict over who would eventually profit from the scheme, who would fund social housing, and what exact provision there ought to be for it and where. Thrown into this was the refusal of UK Land (owners of the shopping centre) to accept the value of the compulsory purchase order on the site. It wanted more money that would reflect the development value.139  Figure 79Later, in April of 2002, SLR was sacked from the scheme and the council commissioned a new development plan with Tibbalds TM2.140 The new scheme would be 'open to question.' Many architects involved with the original plan, including Foster Associates, continued to participate in talks. However, by 2004, they had been pushed out as Ken Shuttleworth's M.A.K.E team was awarded the final contract to draw up a masterplan.141 This plan is finally being implemented.

Figure 79Later, in April of 2002, SLR was sacked from the scheme and the council commissioned a new development plan with Tibbalds TM2.140 The new scheme would be 'open to question.' Many architects involved with the original plan, including Foster Associates, continued to participate in talks. However, by 2004, they had been pushed out as Ken Shuttleworth's M.A.K.E team was awarded the final contract to draw up a masterplan.141 This plan is finally being implemented.

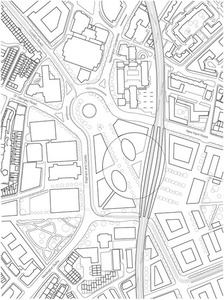

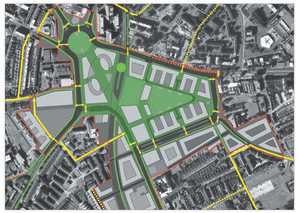

The current Elephant and Castle Development Framework provides a structure for rebuilding and realigning the area within the central sphere of London (see figs 78 & 79). The Elephant has long languished at a peripheral site in the minds of both the commercial developer and a wider public. The framework is part of a wider South Central142 Figure 80 strategy for the Elephant to take on more of the functions and characteristics of the centre. In spirit, it shares much with the early plans of the post-war era; though it is hoped that the fate of the framework will not repeat that of its 1951 predecessor. The public body is, once more, the driving force for change, aiming for, "fabulous buildings and civic spaces,"143 rather than unreliable and unimaginative piecemeal approaches. Once more the Elephant and Castle is being referred to as a Southern Gateway into central London, but the language of comprehensive planning has altered significantly. The framework is littered with a new inclusive vocabulary that stresses, 'deliverability,' 'management,' 'wealth creation,' 'opportunity areas,' 'informed Change,' 'pragmatism,'and, 'sustainability.'144 Southwark Council has set out a structure of what type of developments it would like to see, but, rather than dictate exacting building specifications and design in a top down manner, it will rely on the will, co-operation and good manners of the private sector to deliver within an agreed arrangement of streets, spaces and places oriented around public transportation (see map fig 80).

Figure 80 strategy for the Elephant to take on more of the functions and characteristics of the centre. In spirit, it shares much with the early plans of the post-war era; though it is hoped that the fate of the framework will not repeat that of its 1951 predecessor. The public body is, once more, the driving force for change, aiming for, "fabulous buildings and civic spaces,"143 rather than unreliable and unimaginative piecemeal approaches. Once more the Elephant and Castle is being referred to as a Southern Gateway into central London, but the language of comprehensive planning has altered significantly. The framework is littered with a new inclusive vocabulary that stresses, 'deliverability,' 'management,' 'wealth creation,' 'opportunity areas,' 'informed Change,' 'pragmatism,'and, 'sustainability.'144 Southwark Council has set out a structure of what type of developments it would like to see, but, rather than dictate exacting building specifications and design in a top down manner, it will rely on the will, co-operation and good manners of the private sector to deliver within an agreed arrangement of streets, spaces and places oriented around public transportation (see map fig 80). Figure 81

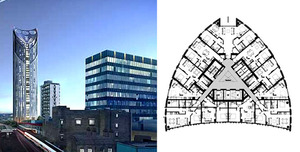

Figure 81 Figure 82 Each site will be put out to tender and in this way a variety of architects can become involved and it is hoped a diverse cityscape will develop. Already, commercial schemes for key sites have emerged and give an indication of the architectural treatment one can expect in the future (see figs 81, 82 & 83).

Figure 82 Each site will be put out to tender and in this way a variety of architects can become involved and it is hoped a diverse cityscape will develop. Already, commercial schemes for key sites have emerged and give an indication of the architectural treatment one can expect in the future (see figs 81, 82 & 83).

The central area of the Elephant and Castle Development Framework, or "core area of opportunity,"145 is divided into distinctive 'character areas,' that acknowledge both a local identity and a future city-wide role for the Elephant. Central to the plan is the extension of the Walworth Road as a pedestrianised shopping street at a similar width to that of Regent Street (see map fig 80 & fig 84). The idea is a clear revision of the original 1951 proposal (see fig 23). The Walworth Road would lead to a new Civic Square, which would be a similar size to Trafalgar Square, formed from the reconfiguration of the northern roundabout into a peninsular (see fig 85). It is anticipated that this will form a commercial hub for landmark office premises and an outdoor space for the whole city to utilise. On the other side of the railway, on the current site of the Figure 83 Heygate Estate, there will be a new Market Square with refurbished railway arches providing both small scale commercial premises and new through ways or desire lines to other areas. Behind it there will be a new Town Park overlooked by rebuilt blocks of mixed tenure studio flats and larger family-sized units (see figs 86 & 87). Contributing to the new community will be a refurbished St Mary's Churchyard with a City Academy and announcing the whole scheme to the rest of London will be twin Eco towers at its heart.

Figure 83 Heygate Estate, there will be a new Market Square with refurbished railway arches providing both small scale commercial premises and new through ways or desire lines to other areas. Behind it there will be a new Town Park overlooked by rebuilt blocks of mixed tenure studio flats and larger family-sized units (see figs 86 & 87). Contributing to the new community will be a refurbished St Mary's Churchyard with a City Academy and announcing the whole scheme to the rest of London will be twin Eco towers at its heart.

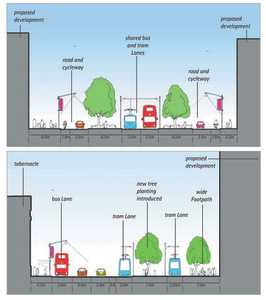

The scope of the framework is arguably as ambitious as the utopian visions announced after the war. The post-war scheme of roads and subways will be completely removed and a straightforward common grade established at ground level for both pedestrians and increased alternative transport modes. There is marked determination that automobile traffic should not dominate the new scheme in the way that it did in the past (see figs 88 & 89). Indeed, there is minimum provision made for the car. Residents and visitors are expected to arrive by tube, bus or tram. New developments will not be encouraged to provide any parking facilities. This approach marks a seismic shift in attitude towards the dominance of the car not only at the Elephant, but across London and the UK that took root in the 1990s.

The transport policies of the early 1990s Conservative government were based on a system of 'Predict and Provide.'146 This process of continual road building was a straightforward response to the growing demand for road use. It essentially followed the trend of growth in car ownership and accommodated it. In its 1989 Roads to Prosperity white paper, the Conservative government had confidently announced plans for a further 1450 miles of new or expanded roads:

...greater car based mobility was seen to both enhance individual liberty and boost the economy- directly through the growth of the motor industry, but also more generally since increased physical mobility helped to liberalize housing and labour markets.147

However, by 1994 large scale road plans had been dropped. The government was prompted to respond to the general realisation that the car and roads were major contributing factors in the destruction of the environment.

Figure 88The 1990s were a period of rapid growth in the popularity and awareness of environmental health issues. The shift in attitudes had come about through the publication of numerous reports into the growing phenomenon of global warming by the European Commission and were cemented on the political landscape by high profile events such as the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The automobile and the lifestyle it promoted was singled out as a major source of greenhouse gas emissions.148 Private transport and its consumption of fuel was threatening environmental sustainability. Moreover, at a local level car dependance meant building over large parts of the countryside for roads and, particularly in the case of London, caused heavy air pollution at street level,149

Figure 88The 1990s were a period of rapid growth in the popularity and awareness of environmental health issues. The shift in attitudes had come about through the publication of numerous reports into the growing phenomenon of global warming by the European Commission and were cemented on the political landscape by high profile events such as the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The automobile and the lifestyle it promoted was singled out as a major source of greenhouse gas emissions.148 Private transport and its consumption of fuel was threatening environmental sustainability. Moreover, at a local level car dependance meant building over large parts of the countryside for roads and, particularly in the case of London, caused heavy air pollution at street level,149  Figure 89which threatened public health and was a contributing factor in the erosion of social sustainability. The orientation of the economy towards the car at urban fringe sites, excluded those without access to it and limited their choice of services. The response to a possible environmental catastrophe was a reassessment in transport policy which, in London, sat parallel to that of the reorganisation of local government.

Figure 89which threatened public health and was a contributing factor in the erosion of social sustainability. The orientation of the economy towards the car at urban fringe sites, excluded those without access to it and limited their choice of services. The response to a possible environmental catastrophe was a reassessment in transport policy which, in London, sat parallel to that of the reorganisation of local government.

The Labour landslide of 1997 brought about a shift in transport policy and what it called a "Consensus for Change." While in opposition the party had unveiled, A New Deal for Transport, its own white paper, which aimed to provide a clear policy for promoting 'sustainable transport' in the face of an 'unacceptable' predicted rise in car use and accompanying emissions.150 The Labour government committed itself to a public transport agenda with road building considered a last resort. It would use policies, such as the fuel escalator151 and road pricing, to persuade drivers to leave the car at home and promote healthier alternatives such as walking and cycling. However, the lifestyles of middle England proved hard to break. Fearful of a backlash from a voting public and business interests, the government relaxed its opposition to car dependance. In the place of sustainability, came 'integration' and 'choice' and new road building, but in London the problem of traffic was too great to ignore and its domestic politics gave scope for greater change.

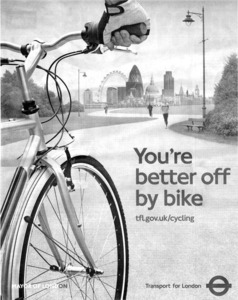

In 2000, London at last regained a central authority for its governance. The Greater London Authority (GLA), with its elected Mayor Ken Livingstone, gained direct control of trunk roads in the capital and has since been pioneering policies unashamedly in favour of public transport and alternative modes of transport (see figs 90 & 91). The GLA, with its subsidiary Transport for London, now has direct control over buses, road prioritisation, cycle networks and, since February 2002, Congestion Charging. The scheme treats central London as one environmental area and has led to significant reductions in traffic levels within the zone.152 Money raised from congestion charging is required by law to go back into improving transport in the city (see fig 92).153 Figure 92

Figure 92

The Congestion Charge has created a new definition of centrality in the city. At present, the Elephant lies at the edge of the zone. Such areas have experienced increased traffic levels as motorists choose routes that avoid the charge. As the road capacity of the Elephant and Castle is reduced, in favour of public transport, it seems likely that in future the zone will expand to take in the Elephant. This would be one possible solution to both easing traffic levels in the area and enforcing the idea of the Elephant as part of the central body of London.

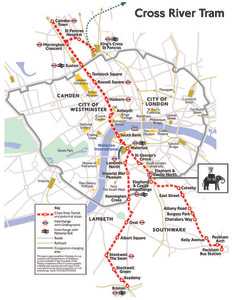

Figure 93One of the consequences of London's improved transportation finances, brought about by traffic charging, is the possible reintroduction of a tram network (see fig 93). This, with other transport modes, would form part of a greater strategic network for London as a whole. It is from this background that the Elephant and Castle Development Framework has emerged and it has a pivotal role to play in the new mobility of the city.

Figure 93One of the consequences of London's improved transportation finances, brought about by traffic charging, is the possible reintroduction of a tram network (see fig 93). This, with other transport modes, would form part of a greater strategic network for London as a whole. It is from this background that the Elephant and Castle Development Framework has emerged and it has a pivotal role to play in the new mobility of the city.

Footnotes

- ↑ Rogers, Richard, 1997. p.105.

- ↑ Ibid. p.114.

- ↑ Building Design, June 7th, 1996. p.20.

- ↑ "The Elephant's Graveyard" Collins, Michael in The Observer Magazine, December 23rd, 2001.

- ↑ Brochure quoted by Redhead, David in The Independent On Sunday, June 15th 1997. p.62.

- ↑ White, Jerry, London in the Twentieth Century, 2002. p.82

- ↑ "Power to the People" Property Week, March 30th, 2001.

- ↑ "Elephant Masterplan Emerges" London Housing, April 2004. Pp.12-14. Returned cards accounted for about 6% of total sent.

- ↑ "Pigs might fly over London's white Elephant." The Architects' Journal, March 18th, 1999 p.8.

- ↑ The Architects' Journal, March 18th, 1999 p.8.

- ↑ Glancey, Johnathan in The Guardian, March 15th, 1999. Pp.12-13.

- ↑ Chris Horn, Southwark Development Director, in London Housing, April 2004. Pp.12-14.

- ↑ "All Change at London's E&C ." The Architects' Journal, May 18th, 2000. p.12.

- ↑ "Foster & Yeang Land 1bn E&C Prize." The Architects' Journal, June 29th, 2000. p.15.

- ↑ "Power to the People." Property Week, March 30th, 2001.

- ↑ London Housing, April, 2004. Pp.12-14.

- ↑ Fred Manson, Southwark's previous Director of Planning in The Architects' Journal, June 29th, 2000. p.15.The private accommodation towers would have been at a high density and achieve a huge financial return for the council.

- ↑ "Elephant Scheme held up by Council row over Profits." Estates Gazette, March 30th, 2002.

- ↑ "New Vision for the E&C ." The Architects' Journal, April 18th, 2002. p.4.

- ↑ "Foster Loses out as Shuttleworth makes E&C mark." The Architects' Journal, June 17th, 2004. p.5. Many architects who worked for Fosters' on 2000 scheme joined M.A.K.E.

- ↑ South Central is an invented collective term used to rebrand the areas of Vauxhall, Waterloo, London Bridge, Bankside and the Elephant and Castle. It is promoted both by the local authority and especially by commercial property developers. See www.londonsouthcentral.uk.com.

- ↑ Elephant and Castle Development Framework, Part One: Role & Purpose, 2004. p.1.

- ↑ Ibid. p.2.

- ↑ Elephant and Castle Development Framework, Part Two: Illustrative Masterplan, 2004. p.14.

- ↑ Docherty, Iain & Shaw, Jon, 2003. p.75.

- ↑ Docherty, Iain & Shaw, Jon, 2003. p.7.

- ↑ Ibid. p.9.

- ↑ Rogers, Richard, 1997. p.119. Rogers argues that pollution caused by cars contributes to the fact that one in seven London children suffers from asthma or another respiratory condition.

- ↑ Docherty, Iain, 2003. p.11. In Docherty's view transport accounts for 25% of all carbon emissions in the UK with road vehicles accounting for four fifths of that total.

- ↑ Ibid. The fuel escalator raised the cost of petrol by 5% each year. It was abandoned after large scale blockades threatened the country in 2000.

- ↑ Transport for London, London Travel Report 2005, 2005. p.7. From www.tfl.gov.uk. 20/01/06. In 2003 traffic levels in the congestion charging zone were down by 33%. That figure remained steady for 2004.

- ↑ www.tfl.gov.uk/tfl/cclondon/cc_benefits 22/06/06.